The Restaurant Investor

The story of Steak n Shake, its new owner, and what it takes for a restaurant to succeed. (And what we can learn from how McDonalds and In-N-Out succeeded.)

This is a long-form article about the restaurant industry and the turnaround of Steak-n-Shake in 2008–2009. It tells the stories of how McDonalds, In-N-Out Burger, and Steak n Shake were founded and have stayed successful for so long. A PDF of the article can be found here. Please enjoy, and checkout the update at the end regarding the Biglari story.

In March, 2008, Sardar Biglari won the most important victory of his life. In an activist campaign to gain control of the board of directors of The Steak n Shake Company, Biglari and his partner received nearly triple the number of votes of the directors they were replacing.

It hadn’t been easy—their proxy fight with incumbent management had been going on for more than six months. Biglari and the entities he controlled first purchased seven percent of Steak n Shake during the summer of 2007. In August, the initial filing was made with the S.E.C. stating that Biglari had been in discussions with management. At this point, as with many activist investors, Biglari hoped that management would be open to his suggestions and criticisms of the company. He was the third largest owner of Steak n Shake at the time, holding more shares than all executive officers and directors combined. Only days earlier, C.E.O. Peter Dunn had unexpectedly resigned, stating his intent to “pursue other interests.” It seemed like the perfect time to reform the faltering restaurant chain.

Yet, after Biglari’s initial meeting with the Board and interim C.E.O., he was denied representation and otherwise rebuffed from any involvement with the company. To management, he was as a nuisance—one that if ignored, would go away. But Biglari was not the kind of investor to be ignored. While continuing to accumulate shares, he launched the first blow in the proxy fight on October 1. Along with an official solicitation to shareholders, Biglari wrote a brief letter outlining his intentions and frustration with the performance of Steak n Shake.

During the proxy fight, Biglari’s demands were relatively mild. His initial goal was to obtain two Board seats—one for himself, and one for Philip Cooley (Biglari’s mentor and business partner). But as the Board continued to fight, and Steak n Shake’s performance continued to decline, he determined that simple representation wasn’t enough. The current Chairman and interim C.E.O., along with the Lead Director, had to go. Biglari launched a website titled “Enhance Steak n Shake” and went as far as buying billboard space in the company’s hometown of Indianapolis.

After months of back-and-forth between Biglari and incumbent management, the minority share owners of Steak n Shake made the overwhelming choice to replace current leadership with Sardar Biglari and Phil Cooley. During the contest, some claimed that Biglari was nothing but a corporate raider, only interested in Steak n Shake to pursue short-term profits at the expense of the company. Now, he would have the chance to prove them wrong.

Of course, this wasn’t the first time Biglari had successfully launched a hostile Board takeover of a public company. Despite his relatively young age of thirty-years, this wasn’t even the first restaurant he had pursued.

Sardar Biglari was born in Iran, eighteen months before the overthrow of the reigning monarchy. His father was a military officer for the deposed Shah, his mother a friend of the royal family. After the Revolution, his father was imprisoned, and both Sardar and his mother were put under house arrest. It was five-years later, in 1984, that they would finally escape after bribing prison guards to let Sardar’s father go. He had once been stationed in San Antonio, Texas, which is where the family settled down. Sardar was seven years old when he arrived in the States and began learning his new language.

It wouldn’t take long for him to find his calling. In Iran, Biglari’s family had a history in the rug business. Since the age of thirteen, Biglari continued the tradition by working at his parent’s Oriental rug store in San Antonio. Not one to be too dependent on others, he knew he would eventually have to make it on his own. He would end up briefly running his own rug store, although his interests would ultimately lay elsewhere.

In 1996, Biglari and a friend started INTX. Networking LLC, a local internet service provider. Refusing to accept any help from his parents, Biglari raised only $15,000 and convinced employees to accept low pay at first in the hopes of a bigger payout later. They had no problems growing the company, and three years after its launch, INTX was sold for an undisclosed sum to Internet America. At the height of the internet bubble, Biglari learned one of his first lessons of investing: it’s always good to sell to over-optimistic buyers. At the age of twenty-two, he was now a millionaire.

Biglari first came across investing while attending college at Trinity University in San Antonio. On a plane ride to Cancun, he opened a book on Warren Buffett, and noticed that they both shared the same birthday of August 30. Enticed, he read on, and Buffett’s rationality and common sense approach immediately appealed to him. That’s when Biglari decided that he wanted to be a professional investor. He read, studied, and researched everything he could get his hands on, and became friends with Philip Cooley, a like-minded finance professor and head of the student-managed investment fund at Trinity.

Three years later, Cooley would accept his invitation to join the Board of Directors of Biglari Capital Corp., Biglari’s new investment management firm. Biglari Capital first launched The Lion Fund, a private investment partnership that initially managed only Biglari’s personal money, in 2000. A year later, on the back of excellent results, he began raising capital from outside investors. Despite falling equity prices from the collapse of the internet bubble, The Lion Fund ended the year up 14 percent.

The word began to spread about Biglari’s fund. It didn’t hurt that he was good at marketing himself — hosting local get-togethers, giving presentations, and receiving good publicity from the San Antonio business press. But it was much easier to pitch investors with great results, and that’s what Biglari focused on. By the end of 2005, the fund had handily beaten the market, and had grown assets under management to a very comfortable size. Up until that point, Biglari had remained a passive investor — purchasing and selling equities, but never getting involved in the businesses themselves. That changed with his purchase of Western Sizzlin in the summer of 2005.

Western Sizzlin is a small chain of buffet restaurants, primarily located in the southeastern part of the country. The company was founded in 1962, and continued to grow until it hit its peak in the nineteen-eighties. The size of the chain has declined ever since. Biglari first took notice of Western when he learned that Jim Verney, the C.E.O. who had just been installed three years earlier in another proxy fight, had done a remarkable job at turning the company around. Four months after their first purchase, The Lion Fund owned 16 percent of the shares. Unlike Biglari’s future battle with Steak n Shake, the Western Board of Directors initially obliged him by giving The Lion Fund two board seats only a month after their first contact. With the absence of other controlling investors, Biglari continued to buy the stock, eventually acquiring almost a third of the company. Soon after, in March of 2006, Biglari and Phil Cooley were appointed Chairman and Vice Chairman as seven board members resigned. In a letter to shareholders, Biglari relayed the new goal of the Western Sizzlin Corporation: “We intend for the entire organization to exhibit an ethos of caring about its shareholders… an ethos that ensures that capital is allocated for obtainable positive results for the benefit of our franchisees, our customers, and ultimately our shareholders.”

Although Western was a well-run, profitable company, the brand didn’t have much potential for growth. Biglari had always understood the power of a good brand. As a boy in Iran, Kellogg’s was so dominant that every cereal was called “Cornflakes.” After moving to the United States, he realized that in addition to Cornflakes, Kellogg’s made all of his favorite cereals. Ever since that moment, he has never forgotten the value of a dominant brand name. If a company’s product holds a special place in the minds of customers, it can not only earn higher profits, but also withstand the inevitable missteps of the company itself.

II.

The restaurant business isn’t an easy one. Because of the industry’s low barriers to entry and simplistic business model, it is appealing to many would-be entrepreneurs. But the actual management of a restaurant is notoriously difficult. The average return on capital for even a well-run restaurant is about 15 percent before taxes. Unless you can significantly differentiate yourself from the competition — which, with the commodity-like nature of the industry, is much easier said than done — restaurants are low on the list of potentially great businesses.

My grandfather, who had been involved in many different businesses throughout his life, always admitted that running a restaurant was the most challenging. “There were always problems,” he would say. “Problems with the employees, problems with the food, and problems with the profits.” Commenting on the industry he had chosen to invest in, Sardar Biglari said that the business “necessitates superior entrepreneurial talent that must fight unremittingly day in and day out and sometimes all day long to attract customers.”

So if restaurants are such a difficult business, then who in their right mind would invest in them? To answer this question, we have to understand what it takes for a restaurant company to succeed. What are the traits and advantages that give some restaurants an edge over others? The following stories are of two restaurants — both with eerily similar beginnings — that took two separate paths, yet still achieved enormous success.

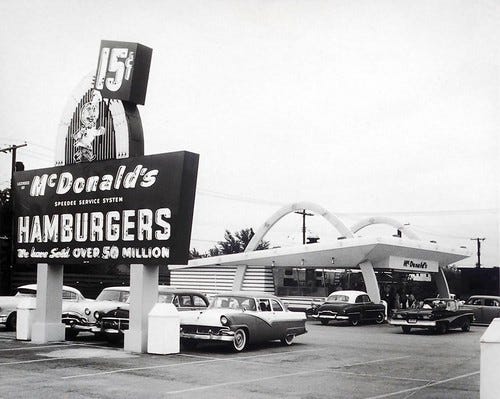

As Ray Kroc sat in his car, he watched a miracle unfold. The parking lot was full, the lines were long, and customers were leaving with an arm-full of food and a smile on their face. Kroc stopped a few to see what was going on: “You’ll get the best hamburger you ever ate for fifteen cents. And you don’t have to wait and mess around tipping waitresses.” He had travelled the country selling milkshake machines, visiting countless restaurants of all types. But he had never seen a merchandising operation like this. It was 1954; fourteen years after the McDonald brothers opened their small burger drive-in in the town of San Bernardino, California.

The brothers — Mac and Dick McDonald — had started the fast-food stand in 1940, but didn’t achieve real success until eight years later. It was then that they turned the kitchen into a mechanized assembly line — with each step in the cooking process being stripped down to its essence and accomplished with minimum effort. They got rid of the carhops and indoor seating, replacing them with a system where customers would order directly through outdoor service windows. By concentrating their efforts on keeping costs down, the brothers could maintain low prices for a consistently good product. This inevitably led to a high rate of customer turnover. “Our whole concept was based on speed, lower prices, and volume,” Dick McDonald recalled. “We were going after big, big volumes by lowering prices and by having the customer serve himself.” By 1954, they had haphazardly licensed ten other drive-ins, many of which were poorly managed and had no consistent system. They were McDonald’s only by name.

This is where Ray Kroc, a spunky salesman from Illinois, entered the picture. Kroc was a visionary. No matter what kind of business he had pursued over his life, he dreamt big. From selling milkshake machines to flipping real estate in Florida, his goal was always to be the best. There was no settling for second place. So when he pitched his franchise idea to the McDonald brothers (he had already tried with Carl Karcher and Harry Snyder), he didn’t hesitate to think big. “Visions of McDonald’s restaurants dotting crossroads all over the country paraded through my brain,” Kroc later recalled. At first, the brothers politely declined. They were content with the decent living they made running just one store in California. Kroc persisted, explaining that he would help open all the stores — doing all the hard work — and the brothers would just sit around and collect royalties. They agreed. A contract was drafted that day, and Kroc was on his way back to Chicago.

Before he could begin selling franchises, Kroc had to build his own McDonald’s to perfect all the procedures. He went fifty-fifty with a friend on a location in Des Plaines, Illinois, which opened its doors on April 15, 1955. All the cost and time saving mechanisms had to be the same — the layout of the griddles and fry vats were essential to the operation’s efficiency. But most of all, Kroc was adamant about maintaining the consistent quality of the food. They had some initial difficulties replicating the San Bernardino store’s success. Leaving the potatoes outside in California, it turned out, produced a completely different french fry than in Illinois. Kroc’s attentiveness paid off: “Ray, you know you aren’t in the hamburger business at all,” one of his suppliers told him. “You’re in the french-fry business. I don’t know how the livin’ hell you do it, but you’ve got the best french fries in town, and that’s what’s selling folks on your place.”

Although the Des Plaines location wasn’t doing as well as the California McDonald’s, it had made money from day one, and Kroc now had the confidence to start lining up franchisees. Just over a year after the 1955 opening, there were already eleven franchised stores across the country. Another year later, in what would become the beginning of a breakneck growth pace, there were twenty-five more units opened.

Through his agreement with the McDonald brothers, Kroc was earning a paltry 1.9 percent of the gross revenues of all McDonald’s franchises and 25 percent of that went to the brothers. (In 1960, despite having system-wide revenue of $75 million, McDonald’s earned only $159,000.) Something had to be done to earn extra income. Harry Sonneborn, the company’s financial wizard, came up with the idea of purchasing the real estate under franchised locations and leasing it back to the operator. Franchise Realty Corporation was set up in 1956 to act as the landlord to current and future franchisees. As the operators began paying ever-increasing monthly rent, Franchise Realty soon became one of McDonald’s biggest generators of profit.

In 1959, the decision was made that the company should build and operate ten or so locations in addition to their franchise operations. To finance the expansion, they received a loan from three insurance companies for $1.5 million in exchange for 22½ percent of McDonald’s stock. After the first McOpCo (McDonald’s Operating Company) store was established, the loan would provide the basis for McDonald’s rapid growth during the sixties.

Despite the new income from Mc-OpCo and Franchise Realty, Kroc was unhappy about his agreement with the McDonald brothers. In 1961, he asked them to name their price, and bought the company and the name for $2.7 million. At the time, he balked at the price and viewed the brother’s offer as outlandish. Yet in hindsight, the buyout would turn out to be one of the best investments Kroc would ever make.

Kroc stepped down as C.E.O. in 1968, but he still played an active role in the company. Despite a bad economy during the seventies, he pressured the company’s leaders to increase the rate of growth. “Hell’s bells, when times are bad is when you want to build!” Kroc screamed to his executives. “Why wait for things to pick up so everything will cost you more?”

At the time of Kroc’s death in 1984, the McDonald’s system had grown to just under eight thousand restaurants in thirty-two countries around the world. Using the same methods that Kroc obtained — and perfected — from the McDonald brothers, the company continues to maintain its role at the top of the fast-food world. In 2008, it narrowly inched-out Subway in terms of the number of total locations — coming in at 31,672. With average sales per store of $2.2 million, McDonald’s remains the undisputed leader with system-wide sales of over $70 billion. That seventy billion in volume came from serving over twenty-one billion customers in 2008 — meaning that, on average, every person on the planet visited a McDonald’s three times last year. Even Ray Kroc couldn’t picture that.

So, aside from great leadership and the luck that is inherent in any success story, how did McDonald’s achieve these results? Examining the company’s history, there are three elements that stand out: their franchising model, their leadership in cost and time efficiency, and their ability to convey those benefits into the minds of customers.

Once you have a good brand and model that works well with customers, the concept of franchising is very appealing to any businessman. You provide the name, image, procedures, product and some training, they do the rest of the work and you receive perpetual royalties. The amount of capital needed to grow a franchising operation is minimal, which makes it even more appealing from a return on investment standpoint.

With McDonald’s, from day one, Ray Kroc made sure that franchising was the main focus. “[T]he corporation is in the hamburger restaurant business, and its vitality depends on the energy of many individual owner-operators,” Kroc reminded his colleagues. “We are an organization of small businessmen. As long as we give them a square deal and help them make money, we will be amply rewarded.” During his tenure at McDonald’s, Kroc maintained a delicate balance between top-down, system-wide standards and a decentralized, entrepreneurial environment at both the franchise and corporate level.

Throughout its history, McDonald’s has been intimately involved in the development of their operator’s locations. By the time Kroc left the company, franchise owners were asked to spend five-hundred hours working in another location first, and to attend Hamburger U, the company’s training facility for managers and operators. At times, the company scouted real estate locations for their operators years in advance.

But the franchise relationship was a two-way street. Over the years, operators developed successful additions to the menu such as the Big Mac, Filet-O-Fish, and Egg McMuffin. In 1963, the marketing idea of two Washington D.C. operators was soon used across the entire chain, and has been promoting the company ever since. Ronald McDonald, the “Hamburger-Happy Clown,” was created by Willard Scott, a local television announcer, to appeal to kids and their families. Always a fan of catchy marketing gimmicks, Kroc loved the idea.

However, without a great concept in the first place, franchising falls flat on its face. The ability of McDonald’s to have both the fastest and most cost efficient procedures gave them a persistent advantage over rival fast-food chains.

In the 1960s, they realized the need for more sophisticated mechanical equip-ment and electronic aids to help speed up the food preparation process and make their products more uniform. The McDonald’s Research and Development Laboratory was established to address these issues. Technicians and engineers worked on everything from a dispenser that gave the exact right amount of ketchup every time, to the Fatilyzer — a testing device that allowed operators to analyze meat shipments as they were delivered. With regard to continually lowering costs and improving operations, Kroc was relentless. “[P]erfection is very difficult to achieve, and perfection was what I wanted in McDonald’s. Everything else was secondary for me.”

But all the cost and operational efficiencies wouldn’t matter if they didn’t bring in more customers. When someone thinks of McDonald’s, it is likely they think of cheap, fast, consistently quality food. (And by quality, I mean a good, not great or healthy meal.) There’s no sitting down and waiting — you order from the wide variety of options, get your food almost immediately, and go.

In Kroc’s autobiography “Grinding it Out,” he succinctly describes some of the reasons why McDonald’s works so well with both customers and franchisees:

We wanted to build a restaurant system that would be known for food of consistently high quality and uniform methods of preparation. Our aim, of course, was to insure repeat business based on the system’s reputation rather than on the quality of a single store or operator. This would require a continuing program of educating and assisting operators and a constant review of their performance. . . . the key to uniformity would be in our ability to provide techniques of preparation that operators would accept because they were superior to methods they could dream up for themselves.

In the minds of customers, creating a uniform and consistent product is one of the most important aspects of McDonald’s success. No matter where you go, once you see the ubiquitous “golden arches” you know exactly what you’re going to get. Especially when you’re in a hurry, why take the chances with someplace else? They’re not known for high quality food, service, or atmosphere — but as evident from the enormous amount of customers they serve, McDonald’s is the clear leader in cost, speed and consistency.

The story of In-N-Out Burger begins with newlyweds Harry and Esther Snyder moving from Seattle to Southern California. They were starting new lives together, and Harry was following his dream of going into business for himself. It didn’t take long for him to come up with an idea: a hamburger stand. It seemed like a perfect opportunity with both the rapid growth that Southern California was undergoing and the disproportionate number of people who drove cars there. In particular, Harry wanted to open a drive-through — a relatively unheard-of concept at the time. “We really have to have a place where people can get their sandwiches and go,” he said. On October 22, 1948, Harry and Esther opened the first In-N-Out Burger in Baldwin Park, San Gabriel Valley. (Only forty-five miles east of where the McDonald brothers had just refurbished their drive-in.)

From the beginning, Harry had a very particular philosophy about what kind of business they were in. In-N-Out would serve the freshest, highest quality burgers and fries, and be relentlessly focused on their customers. This meant treating employees as partners in the business, and never growing for the sake of growth. The system was based on three words: “Quality, Cleanliness, and Service.” While starting the first location, Harry sought advice from Carl Karcher, who by 1948 had built a small chain of hot dog stands in Los Angeles called Carl’s Jr. “It’s so important to make people feel special,” he told the Snyders.

The drive-through concept ended up making a huge difference in the chain’s initial popularity. In the late forties and fifties, the rise of the fast-food drive-through coincided with the rise of car culture and the establishment of the interstate highway system across the country. In-N-Out was one of the first, if not the first, electronic drive-throughs in the world. Instead of employing carhops, Snyder invented a simple two-way speaker box that was connected to the kitchen. Customers would drive in, place their order at the box, and drive to the other end of the building to pick up their food. This may not sound out of the ordinary today, but in 1948, most customers were completely unfamiliar with the system.

Although the drive-through system was what gave In-N-Out its name, the real reason that customers flocked to the restaurant was, and still is, its food. Their simple, unchanging menu is famous in the industry: three burger items, french fries, soft drinks, and milkshakes. The menu lineup remains unchanged, with a few minor exceptions, from the original menu in the forties. Not many restaurants can pull off such a limited selection. But In-N-Out more than compensates by making sure their product is the best in the business. With a motto of “Quality You Can Taste,” In-N-Out isn’t “fast-food” in the traditional sense. The burgers aren’t prepared until a customer places their order, and it can be customized to their heart’s intent. Unlike most fast-food restaurants today, In-N-Out has always used fresh, one-hundred percent additive-, filler-, and preservative-free beef for their burgers. As others began to use cheaper concentrated ice milk mixtures, they refused to use anything but real ice cream in their milkshakes.

Despite restricted menu choices, the made-to-order ability to customize your food has added to the company’s cache. The origins of the famous “secret” menu of In-N-Out are unknown. Of course, among locals and fans of the chain, the unofficial menu isn’t really a secret. Mostly invented by customers over the years, the menu items include the 4x4 (a burger with four meat patties and four slices of cheese), Animal Style (a burger fried in mustard with all the available condiments), and the Flying Dutchman (two meat patties, two slices of cheese, and no buns).

At any company, it is the employee’s job to deliver on the promise of high quality. But In-N-Out has a history of treating their employees a little differently than most retail establishments. Since founding the company, Snyder offered his young workers higher pay, benefits, and the ability to be continually promoted within the chain. In fact, his initial motivation for expanding from the first location was to accommodate new hires as senior employees refused to leave. Hard work was always rewarded, and this meritocracy established in the early days was ingrained into the company culture. “They take your orders and make your food,” said Esther Snyder. “They’re so important, so you want to have happy, shining faces working there.” In 2008, starting pay for all new associates was ten dollars an hour — over thirty percent higher than the California minimum wage. Store managers of In-N-Out, many of whom worked their way up from the very bottom, make over $100,000 a year.

To help reinforce their culture in the ranks of the growing chain, the company started In-N-Out University in 1984. The University was a large-scale management training program where upper- and lower-level employees could receive instruction and learn how to run a unit in a real-world environment. The program reinforced its management practices such is communication skills, methods for motivating associates, and positive attitudes. The University was just one of many efforts to maintain Harry Snyder’s basic principles as the company grew.

It was never his intention to build a large chain of In-N-Out Burgers. After finishing the second location in 1951, growth continued at a sluggish pace over the next few decades. The company focused on putting the stores in highly visible, heavily trafficked areas, and rarely put more than one drive-through in the same market. The Snyders later realized that, although they prided themselves in serving every kind of customer, building locations in higher income areas usually led to higher sales. By being selective and spacing their restaurants so far apart, it only made them more desirable in the minds of customers.

It wasn’t just their desire to maintain the company’s culture that suppressed growth. Harry Snyder hated debt, and from the beginning had insisted on using cash for all transactions. For a good part of In-N-Out’s history, they owned the real estate free and clear under every location. Eventually, as the chain was passed on to Harry’s son Rich, faster growth prevented the purchase of real estate for every new store. Currently they own roughly 60 percent of their locations.

They have flat-out rejected the idea of ever franchising the In-N-Out concept. Frequently refusing franchise requests (at times up to thirty a week), the Snyders saw it as a surefire way of losing quality control. By 1990, there were sixty-four locations, taking in sixty to seventy million in sales annually. Commenting on rumors of a potential public offering, Rich Snyder denied there was any possibility. “I think it would be too difficult to maintain quality control. I like the fact that I can visit all of our locations and they all know me. It’s kind of like what they say about farming — the best fertilizer there is in the field is the farmer’s footprints.” In-N-Out would continue to be a private, family-owned business as long as it existed.

Because of the good word of mouth that spread about In-N-Out, they needed little in the way of marketing. Any actual advertising was small scale. The Snyders believed that if their product was good enough, the customers would eventually hear about it. Stacy Perman, in her book “In-N-Out Burger,” describes one example of customers serving the role of marketer:

The chain’s regulars assumed the responsibility of bringing in a constant stream of new devotees, an act generally referred to as “the conversion.” The deed had the feel of bestowing membership into a club that seemed at once exclusive and egalitarian. The prototypical conversion story goes something like this: “I was one of the converts,” proclaimed Angela Courtin . . . “It is the great class equalizer. Look inside! You get everybody here: middle-class skateboarders and Beverly Hills ladies, ethnic families and day laborers, all eating in the same restaurant, at the same price point, and with the same three options.”

But it wasn’t just the food and the experience that people talked about. Starting with things like the “secret” menu, the mystique surrounding the chain helped the In-N-Out story spread. (Why are there two crossing palm trees in front of every store? Why are there Bible verses on the bottom of every cup? Where are they going to expand to next?) The fact that the restaurants were popular with celebrities didn’t hurt. From Bob Hope, who tried in vain to invest in the company, to actors and actresses at Vanity Fair’s annual Oscar party (they began hiring one of In-N-Out’s cookout trailers in 2001); it was a fast-food joint that was popular with everyone. When in 2002 In-N-Out opened a new drive-through in the town of Oxnard, California, there were nine-hundred applicants for only seventy positions. Although exact figures are impossible to come by, in 2005 there were two-hundred locations making around $350 million a year. With average unit sales of $1.8 million, they were just short of McDonald’s $2 million figure at the time. Without serving breakfast and having only three primary menu items, the financial success of In-N-Out is all the more impressive.

Just as we did with McDonald’s, let’s take a look at some of the reasons why In-N-Out became so successful. In this case, the general qualities that give them an edge are very basic: intense focus, simplicity, and a story that spreads.

“Keep it real simple,” Harry Snyder was fond of saying. “Do one thing and do it the best you can.” In-N-Out understands what they do best — quality and service — and they focus exclusively on it. There are no sideshows. That’s why, starting with the first location under Harry’s leadership, employees are treated like partners in the business. That’s why, over their sixty years of operation, they never caved into using cheaper ingredients for higher margins.

Intense focus doesn’t necessarily lead to simplicity, but in order to focus on quality, In-N-Out decided to keep things simple. Over the years, various customers and employees of the chain have questioned the limited menu. Why not add a few items to keep up with the times, like a salad or chicken sandwich? Because they focused on making the best hamburgers at a reasonable price, In-N-Out believed that adding new items would only detract from this goal. Keeping things simple made it not only easier for the company, but easier for customers. There isn’t much to decide when looking at the menu, and each item is as basic as can be. People know what to expect from In-N-Out — great burgers, and great service.

Cult status among customers may not seem like a conscious advantage. But how did they achieve that status? In their book “Made to Stick,” Chip and Dan Heath describe the elements that allow ideas to spread. The story of In-N-Out Burger shares almost every one of them. Simplicity is one element. The mystery surrounding the chain is another. In the book, the Heath brothers explain why a mystery gets people’s attention: “Mysteries are powerful, [Robert] Cialdini says, because they create a need for closure. ‘You’ve heard of the famous Aha! experience, right?’ he says. ‘Well, the Aha! experience is much more satisfying when it is preceded by the Huh? experience.’ ” Emotional (another element), passionate fans of In-N-Out can’t help but tell the chain’s story to anyone who will listen. And when a “convert” hears about the great food, simple menu, and air of secrecy, they are instantly intrigued. That’s a kind of marketing that even McDonald’s can’t match.

III.

Investing, as many people see it, is the buying and selling of stocks, bonds, and other securities. But the job of an investor is really to find the best place to allocate available capital. When looked at in that regard, all businessmen are investors. “I’m a better investor because I am a businessman,” goes the oft-repeated quote by Warren Buffett, “and a better businessman because I am an investor.”

Let’s say the owner of a restaurant chain decides to build a new location. What she’s really doing is making an investment decision. And that decision has to be put in the context of the other available options at the time. Could she put the same amount of money to better use by improving the current restaurant operations? Maybe neither option is great, and she could pay the money out to herself and the other owners. Or maybe the owner is extremely confident in her entrepreneurial skill, and she thinks that starting a carwash in the same location is a better use of capital. This is the familiar concept of “opportunity cost” that is taught in every economics class.

So when Sardar Biglari took control of Western Sizzlin, he immediately began reorganizing it from the perspective of an investor. Cash flow from the restaurant operations would be allocated to the best and highest use of capital (assuming Biglari fully understood the opportunity).

Western, like McDonald’s on a much smaller scale, is a franchisor. Out of their one-hundred-two restaurants, only five are owned by the company. As mentioned in Part II, the franchising business can be very lucrative. Despite Western only receiving a 2 percent franchise royalty, it was where a majority of their cash earnings originated. Biglari reiterated the views of Jim Verney, President of Western at the time, and put the focus on cutting costs and supporting the franchise base. “We want to help our franchisees so they can build and maintain customer loyalty, which in turn can increase their profits,” Biglari told shareholders. “Our company’s energies will be centered on answering the inquiry: How can we help our franchisees?”

But franchising was only a small part of the new direction Biglari would be taking the company. The new goal, in accordance with the investor mindset, was to maximize intrinsic value per share. Cash would only be reinvested in restaurants if they could produce returns higher than other available opportunities at the time. In order to more clearly separate the different segments of Western, Biglari reorganized it in the form of a holding company. Much like Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, the holding company structure provided a decentralized, hands-off approach to managing “investments.” Each of the “functions” of Western would now operate in their own separate subsidiary. The Western Sizzlin holding company would still own them, but managers would run them as if they were separate businesses. Any cash that was leftover after all obligations would go to the holding company where Biglari could allocate it as he saw fit.

The company would organize into four main subsidiaries: Western Sizzlin Stores, which managed the five company-owned locations; Western Sizzlin Franchise Corp., which ran all franchising operations; Western Investments, a new segment that managed both public equity investments and a private investment fund; and Western Properties, a new entity that owned their real estate investments. Later, cash would be allocated to higher return opportunities like Steak n Shake and a profitable joint venture in a concept called Wood Grill Buffet.

After Verney left the company in 2008, Bob Moore, a former executive of Whataburger, was put in charge of all restaurant operations. His focus would be to revitalize the Western Sizzlin brand and expand their successful Wood Grill joint venture. Despite the number of locations falling by thirty-eight, from 2005 to 2009, pre-tax cash earnings from restaurants increased from $1.7 million to $1.9 million. (Including the “look-through” earnings of Wood Grill, cash earnings were even higher at $2.2 million.) Even with declining sales from both owned and franchised restaurants, the intrinsic value of Western Sizzlin had undoubtedly grown.

Now Biglari had a template — a frame of reference in his mind that despite being in a hard business, a profitable brand name could ultimately be fixed with good management. Viewing the business like an investor ensured that resources would flow to the most useful endeavor. The only catch — and there’s always a catch — was that the company had to be stopped before it reached the point of no return.

IV.

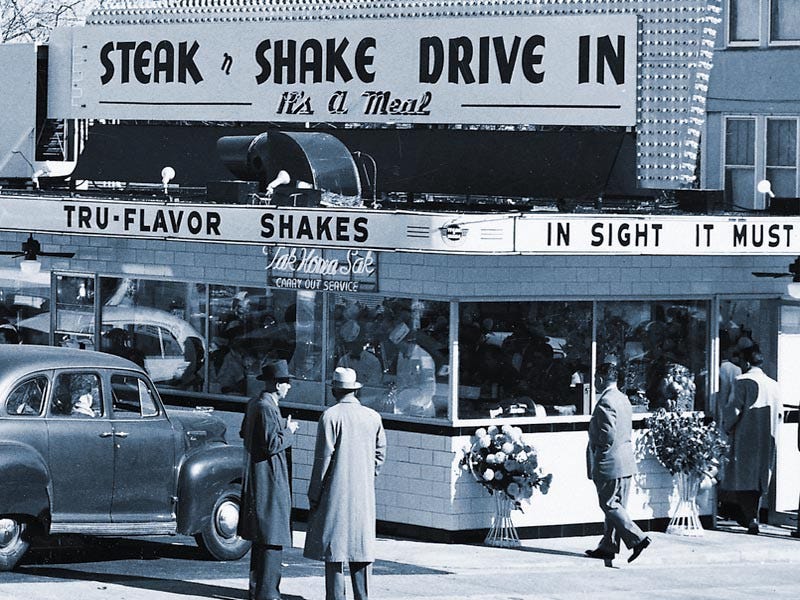

The first Steak n Shake was founded by Augustus Hamilton Belt in 1934. “Gus” Belt was known as a character — a man with a strong, individualistic personality. He was the kind of person who other people told stories about. “If you believed half the stories that were still circulating around Steak n Shake fifteen or more years after his death,” said Bob Cronin, C.E.O. of the company in the 1970s, “you could see you were dealing with somebody unusual — sort of halfway between Will Rogers and James Cash Penney.” But most of all, Belt was a businessman. After a string of unsuccessful ventures, he managed to acquire a Shell Oil station on Route 66 in Normal, Illinois. The station was eventually turned into a Shell’s Chicken, where Belt’s wife would cook chicken for travelers who stopped to buy gas. “Fill ’em up outside, then fill ’em up inside,” was his idea.

As the business became increasingly successful, Belt found himself more and more drawn to the challenges of the restaurant industry. He realized that although hamburgers had become extremely popular with the American public, no one had yet invented the perfect burger. Not a cheap, low-quality burger, but one that people were willing to spend a little extra on. “I’m going to start a drive-in. I’m going to have the finest hamburger in the country and a real, honest-to-goodness milkshake.” Belt took out a loan to convert the Shell station into a functioning restaurant, and with that, the first Steak n Shake was born.

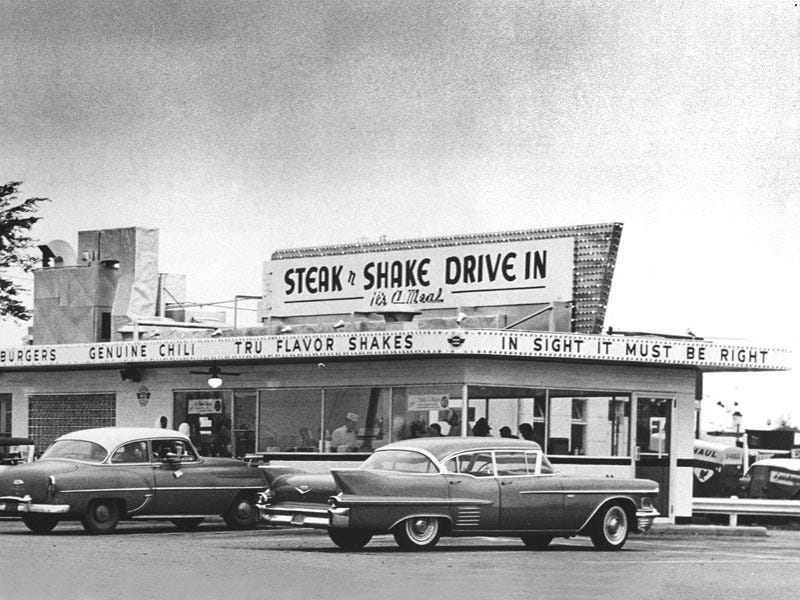

The store was a hit. After Belt knew that he had a winner, he opened a second walk-in store in Bloomington, Illinois. The quality of the food was very important to Belt. He bought the best meat in Illinois, from the Pfaelzer Brothers of Chicago. It was delivered three times a week to each restaurant. The typical burger mix at the time ranged from chuck to cast-off lean and fat beef, but Belt grinded filet and sirloin into the mix. Without the benefit of modern measuring devices, he tested and perfected the correct ratio of fat content: eighty percent lean, twenty percent fat. He named the sandwich “Steakburger.” Restaurants at the time had sanitation problems, so Belt made sure that customers could watch employees grinding the juicy steak cuts into hamburger and putting them on the grill. “In Sight It Must Be Right” was displayed on the outside of the building. The condiments were of high quality too — Belt introduced the idea of cutting pickles vertically to enhance the burger experience: “I don’t like to find all the relish and mustard and pickles in the middle of the sandwich. You don’t get to them soon enough. You ought to be able to taste pickle in every bite.” He personally tested out many different types of fries, and decided that thin-cut, shoe-string potatoes were better than the thick-cut variety.

The Steak n Shake menu started out simple, with four main items: steakburgers, chili, fries, and milkshakes. Other items like grilled cheese and egg sandwiches were less popular. Once, Belt was asked by one of his suppliers to add a pork sandwich to the menu. He pointed to the board and said “Young man, see that board? It has made me over a million dollars, and I’m not about to change it.”

Good service was another inevitable for Belt. According to employees, he was a great trash inspector. He carefully examined waste-baskets and plates returned from table service, looking to see what customers weren’t eating. He wanted to make sure they got their food fast, and were on their way. “Three turns per hour” — twenty minutes per customer — was his motto. While visiting a small chain of restaurants in Denver, he noticed they had the slogan “Tak-Homa-Sak” for their take-out service. With permission from the president of the stores, he appropriated the name. To this day, Tak-Homa-Sak is synonymous with Steak n Shake take-out. It was only much later — after Belt’s death — that curb service and then drive-throughs were added.

During the early 1940s, the war threatened every restaurant business as supplies were severely rationed, and many basic food staples were unavailable. Herb Leonard, a supervisor at Steak n Shake at the time, commented:

Sugar, coffee, beef — all the essentials were hard or impossible to get in a steady way. What were we suppose to do? Have no food for the customers? We had a choice — find a way to get the food or close. … [B]eef was the biggest problem — all of it was going to the military. Gus bought his own cows. He got a 600-acre farm. Yes, we did bootleg cattle. Gus sweated over it, and took responsibility for it all himself. Nobody liked it but we did what we had to.

Belt was fanatical about serving his customers, and instilled that attitude into Steak n Shake’s culture over the first two decades of its growth. After Belt’s death in 1954, his wife Edith took over the company. Over a period of fifteen years, she expanded the store base from twenty-one to fifty-one, but kept the Steak n Shake formula unchanged. In 1969, she sold her controlling interest of 53 percent to Longchamps, a New York restaurant chain, for $17 million.

Only three years after Longchamps acquired the company, they were accused of negligence by dissident shareholders, and sold their interest to the Franklin Corporation, a holding company run by Robert Cronin. Initially unfamiliar with the brand, Cronin became enamored with Steak n Shake. He firmly believed that the basic formula that Gus Belt developed should remain the same. “It was the clean-swept black and white look,” he recalled, “the good, flattened steakburgers, the friendly service, the china plates on the tables, and the creamy, homemade milkshakes whirling around there before your eyes. Those were the things that made customers head in the front door and come back again and again.” Cronin’s leadership would span ten years, when the company was sold again to Ed W. Kelley.

Through the financial ups and downs of their history, the Steak n Shake brand remained strong. An American legacy, Steak n Shake is the fourth oldest restaurant chain in the world. (In case you’re wondering, the three oldest chains, in order, are A&W, White Castle, and Krystal.) It is a testament that during the inflationary period in the 1970s, they were able to pass most cost increases onto customers. Between 1971 and 1976, menu prices increased 37.5 percent versus a 43 percent change in the consumer price index.

While much less successful than both McDonald’s and In-N-Out, the Steak n Shake brand has tremendous appeal in the markets they serve. Their place in the restaurant industry is somewhere between fast-food and casual dining. Customers can order through take-out, drive-through, or be waited on while they’re served on china plates with real utensils. People know they’ll get great food and a good experience for fast-food-like prices. As long as Steak n Shake maintained the quality and value of their four main products, customers would continue to love them.

The nostalgia factor was another reason for customer infatuation. Like In-N-Out, many older customers connected Steak n Shakes with the good times they had in their past. Celebrities were fans — Hugh Hefner, Dick Clark, David Letterman. The film critic Roger Ebert has been a lifelong fan, writing in the seventies and today about his younger years at the chain.

From 1981 through the nineties, E. W. Kelley ran Steak n Shake as Chairman of the Board of Directors. Despite going through a spate of different C.E.O.s (including both board members who would later be voted off in the proxy fight), Kelley managed to hugely expand the company’s reach. He began playing a less active role in 1998, five years before he passed away.

Leading up to Sardar Biglari’s proxy fight with management, Steak n Shake’s financials were falling apart. Store sales had declined for years, and were now leading to losses. The company had a relatively pristine history of profitability — up until 2008, their only annual operating loss occurred once in the mid-eighties. It was clear, to everyone but the management team, that something drastic had to be done.

Sometimes, not only is it easier for an outsider to see the flaws in a business, but it’s easier for them to take the action necessary to solve them. Incumbent management had the best intentions, but they were blinded by the fact that their actions had been successful in the past. Andy Grove, co-founder of Intel Corp., calls this the “inertia of success”:

Senior managers got to where they are by having been good at what they do. And over time they have learned to lead with their strengths. So it’s not surprising that they will keep implementing the same strategic and tactical moves that worked for them during the course of their careers — especially during their “champion season.”

Things can only work out if management realizes their problem, and adapts as necessary. “If they can’t or won’t,” explains Grove, “they will need to be replaced with others who are more in tune with the new world the company is heading to.”

Trapped by the inertia of their previous success, Steak n Shake management continued unabated. After all, since they started playing a more active role in 1998, 207 locations were added, sales grew by $358 million, and the book value of the company grew by 163 percent. Sounds great, right? It could be — but these figures have to be put in the proper context. When looked at from the view of an investor, this growth came at a heavy cost. Over the nine year period ending 2007, a total of $368 million was spent growing the chain. This means that, for every dollar of sales growth, Steak n Shake invested $1.03. As I mentioned in Part II, a typical well-run restaurant achieves a return on investment of around 15 percent. To pass that hurdle rate, the company would have to attain profit margins of over 15 percent. Those are margins that the average McDonald’s location (the industry-wide leader in cost efficiencies) has trouble matching. The growth of Steak n Shake clearly failed to meet its opportunity cost.

But after Biglari and Phil Cooley took over the board, they found the business was in much worse condition than imagined. In addition to increasing losses, the covenants on Steak n Shake’s debt had been breached. Not his initial intention, Biglari was obligated to take the role of Chairman and C.E.O. He immediately moved to renegotiate the debt provisions, where lenders agreed to give them some breathing room as long as they paid off $10 million of loans. But the company had less than $1 million in cash to spare. Biglari commissioned a tax study that almost immediately found $13 million in tax receivables. Apparently the prior management team wasn’t very creative either. If Biglari hadn’t taken over the company, Steak n Shake may have ended up in bankruptcy.

Once the initial fires had been put out, Biglari moved his attention to the company’s culture. He halted the construction of new stores, and let shareholders know that the future of Steak n Shake’s growth would lie in franchising. Like the structure of McDonald’s, a controlled network of owner-operators would be better incentivized to make improvements to the chain.

Corporate-level expenses had also gotten out of hand in recent years as an ivory-tower mentality developed among management. After Biglari took over, any superfluous costs were cut, which would initially save the company around $20 million a year. One of the representative stories he told involved cutting the number of colors on their printed paper-cups from two to one. The measure would save a lot of money, and customers likely wouldn’t miss the small dots of red on their to-go cups. “We have been, and will be, demons on cost!” he said at the annual meeting. From then on, Biglari wanted current and future managers to be the best in the business. If managers were performance- and ownership-oriented, they wouldn’t need to be told to be frugal.

To stem the perennially declining sales, as costs were cut, savings were passed on to customers. When the economy got worse, prices were dropped and store traffic shot up. A simpler, redesigned menu emphasized their core items — burgers, fries, milkshakes and chili — which accounted for 80 percent of sales. “We want Steak n Shake to be best-in-class in product, in menu, in customer metrics, and in financial returns,” Biglari told shareholders. “Every day, roughly a quarter of a million people go through Steak n Shake restaurants; the quality of their overall experience will ultimately determine whether they will increase or decrease their number of visits.”

As members of the old management team left the company, new managers were hired to revitalize the chain. While Biglari may have little experience operating a restaurant company, his new team of executives more than compensated: positions ranging from Operations Excellence to Cost Management were filled with hires from Friendly’s, Wendy’s, and Burger King. Only a year after Biglari’s fund had taken over the board, the changes he initiated were having an immediate positive affect. For the first time in over two years, quarterly sales of Steak n Shake stores were up over the year-ago period. In the same quarter, the company reported its first profit in more than a year-and-a-half.

On August 13, 2009, Steak n Shake announced it was acquiring the Western Sizzlin Corporation for $23 million. Once the deal closes, both the companies that Biglari controls will be under the same umbrella. Like Western, Steak n Shake is now organized as a holding company with each function operating as a separate, but wholly-owned business. The goal of maximizing per-share value now meant that only profitable growth would be pursued.

From little more than a $1.8 million stake in a small chain of buffets, Sardar Biglari was now managing a holding company with a market value of more than $340 million. Though the company will likely end up growing through businesses outside the restaurant industry, the Steak n Shake brand will continue to be its figurehead. And whether or not they thrive depends on if they can keep customers coming in the door. If the success of McDonald’s and In-N-Out Burger are any indication, a well-run restaurant chain like Steak n Shake can be both popular and profitable.

The Steak n Shake Company is now on solid footing. But the actual turnaround, one that may leave the company unrecognizable from its prior form, has just begun. “Naturally,” says Biglari, “we have a fairly lengthy journey before reaching our goals. We will do what it takes to prevail.” ♦

Update: July 16, 2010

In November of last year, I wrote “The Restaurant Investor” about Steak n Shake, Sardar Biglari, and what it takes for a restaurant to succeed. In the article, I mentioned that Steak n Shake (now Biglari Holdings) was on solid financial footing and that Biglari would likely start pursuing a holding-company strategy by investing excess cash flow into better opportunities. While this did happen, a few other “revelations” came up over the past six months that changed my view on the company. Anyone who follows BH already knows what I’m talking about, but below I’ve included my thoughts on the situation from my most recent letter to investors:

* * *

Most everyone has heard of the “Type A” and “Type B” personality classifications. In Dan Pink’s book Drive, he adapts MIT management professor Douglas McGregor’s ideas to put forth two more classifications: Type X and Type I. Type X behavior is fueled by extrinsic motivation — external rewards like money and recognition. Type I behavior is fueled by intrinsic motivation — the inherent satisfaction of the activity itself. “I don’t mean to say that Type X people always neglect the inherent enjoyment of what they do, or that Type I people resist any outside goodies of any kind,” Pink says. “But for Type X’s, the main motivator is external rewards. Any deeper satisfaction is welcome, but secondary. For Type I’s, the main motivator is the freedom, challenge, and purpose of the undertaking itself. Any other gains are welcome, but mainly as a bonus.”

Pink lists some well-known examples of both types: Warren Buffett, Oprah Winfrey, and Bruce Springsteen are Type I’s. Donald Trump, Jack Welch, and Simon Cowell are Type X’s. So it’s clear that both personalities can be successful. People can also change over time. But Type I’s almost always outperform in the long run. They’re also the people you want working for you.

On April 30, Biglari Holdings announced that its new compensation agreement with CEO Sardar Biglari would provide him with 25% of the gain in Book Value over an annual hurdle rate of 5%. So if the Book Value of the company went up 13%, Biglari would receive 2% of the company’s equity. At its current size, that amounts to around $7 million, including his regular salary.

In and of itself, this compensation agreement isn’t inherently bad. It’s a typical “pay for performance” scheme that many private investment funds use, including our own. (In fact, Biglari’s hurdle is slightly more generous than ours, but thankfully I haven’t had any complaints — yet.) I won’t delve into the more technical reasons I dislike the agreement — other than to say that a public company is not comparable to a private investment fund for a variety of reasons. I think the bigger implications are with the revelation of Type X behavior and how it affects the culture and future strategy of the company.

Type X behavior is fairly common among the CEOs of public companies. So it’s obviously not a disaster. In this particular case however, I think it permanently damages reputation. Aside from Warren Buffett’s history of good deeds, it gives people (shareholders, company managers, etc.) comfort that he isn’t in it for the money and is on equal financial footing with other partners. The strategy of Biglari Holdings is also that of “growth through opportunistic acquisitions.” Acquiring companies when you have a reputation for selfishness and hostility can be a difficult undertaking. Also, regarding the people already working for Biglari Holdings, this behavior may have the effect of changing company culture for the worse.

Notes

The biography of Sardar Biglari was compiled from the following sources: Aissatou Sidime’s article “Fund manager finds success at early age” (San Antonio Express-News, May 29, 2004); Interview with Sanjeev Parsad (Oct. 27, 2004); Articles by Mike W. Thomas (San Antonio Business Journal, 7/27/01, 4/2/04, 3/22/06).

Many of Sardar Biglari’s views on his investments were obtained from his letters to the shareholders or partners of Western Sizzlin (2005–2007), Steak n Shake (2007–2008), and The Lion Fund (2001, 2005–2008).

Ray Kroc tells his story of building McDonalds in Grinding it Out (New York: St. Martin’s, 1977).

The history and culture of In-N-Out is examined in detail, along with many other restaurant stories and anecdotes in In-N-Out Burger by Stacy Perman (New York: HarperBusiness, 2009).

All financial figures for Western Sizzlin and Steak n Shake are from their S.E.C. filings. “Cash earnings” are operating income + depreciation and amortization — capital expenditures. Any 2009 figures are for the twelve-month period ending September 30, 2009.

The Steak n Shake story is told in the book Selling Steakburgers by Robert Cronin, the C.E.O. of Steak n Shake from 1971 to 1981 (Carmel: Guild Press of Indiana, 2000). Information about the turnaround was found in Sardar Biglari’s investor letters and the meeting notes of Jim Gillies.

The quotes from Andy Grove are from his book Only the Paranoid Survive (New York: Doubleday, 1996).