Fumbling the Future at Xerox PARC

“There is a wide difference between completing an invention and putting the manufactured article on the market.” — Thomas Alva Edison

In this week’s New Yorker, Malcolm Gladwell writes about innovation and how Xerox PARC failed to profit from the many incredible inventions that came out of its lab. (You can read the summary here.)

PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), located on the Stanford University campus, was founded in 1970 as a division of Xerox Corporation. They were an R&D lab that Xerox planned to use to both create new products and augment their current ones. They were tasked with creating "the office of the future." In the mid-1970s, almost half of the world's top 100 computer scientists were working at PARC. Within five years of its founding, PARC had developed a wide array of important computer technologies, including the following:

Xerox “Alto”— the first personal computer with a mouse and graphical user interface (GUI) that included windows, icons, and pull-down menus.

A WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) text editor.

Computer generated graphics.

An Ethernet local-area-network.

Laser printing.

In Everett Roger's book Diffusion of Innovations, he uses Xerox PARC as a case study in the "commercialization" phase of the innovation-development process. What led the engineers and scientists at PARC to such an amazing track record? Rogers breaks it down as follows:

Outstanding R&D personnel. Several key R&D employees moved to PARC from nearby SRI International, where they had been working under visionary computer scientist Douglas Engelbart. It was around that time that funding to SRI from DARPA, NASA, and the Air Force began to diminish.

Management style that was conducive to creating technological innovation. Led by Dr. Robert Taylor, PARC encouraged the free exchange of technical information among the research workers. Their regular meeting room was equipped with beanbags, and the walls were lined with white boards. There was little hierarchy in PARC, and resources were plentiful.

R&D employees used the innovations that they created in their daily work.

Timing. The time was ripe for technological innovation in personal computing. A crucial prior innovation, the microprocessor, had recently been invented at nearby Intel Corp. Rapid advances in miniaturizing semiconductor functions, with a corresponding decrease in price per unit of computer memory, occurred in the early 1970s.

For anyone not familiar with the history of the computer, the question is obvious -- if the above is true, why don't we all have Xerox computers and Xerox operating systems in our homes right now? The simple answer is that although Xerox PARC invented them, they failed to commercialize and market most of their best discoveries.

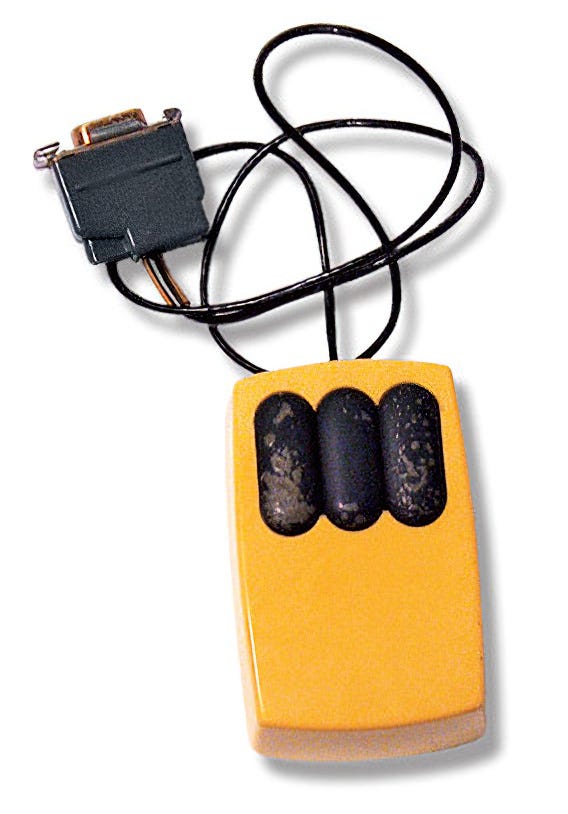

In Gladwell’s article, he makes the distinction between the inventions created at PARC and the adaptations of those inventions by Steve Jobs and his team at Apple. The mouse that the PARC engineers designed cost $300 to build and would only work for two weeks of use. The mouse that Jobs contracted to design and eventually distribute with the Macintosh cost less than $15 to build and was much more functional and durable for a typical user. This difference, Gladwell claims, is not trivial. "It is the difference between something intended for experts, which is what Xerox PARC had in mind, and something that's appropriate for a mass audience, which is what Apple had in mind." In other words, Xerox created a breakthrough sustaining innovation and Apple adapted and packaged that technology into a disruptive innovation.

Gladwell concluded that although PARC was a great place to research and design cutting-edge innovations, it was indeed a bad place to commercialize them. "For an actual product, you need threat and constraint -- and the improvisation and creativity necessary to turn a gold-plated three-hundred-dollar mouse into something that works on Formica and costs fifteen dollars."

In his case study, Rogers lists the following reasons that Xerox ultimately failed to take the final step of commercializing the technologies developed at PARC: (Adapted from the book Fumbling the Future by Douglas Smith and Robert Alexander.)

Xerox was the leading company in the paper copier business, and it perceived itself as only in the office copier business, not in the personal computer business. In Gladwell's words, "Xerox was a multinational corporation, with shareholders, a huge sales force, and a vast corporate customer face, and it needed to consider every new idea within the context of what it already had." This is why one of the only innovations it did end up using was the laser printer.

No effective mechanisms were created for technology transfer from Xerox PARC to the manufacturing and marketing/sales divisions of Xerox.

The button-down organizational culture at Xerox's Stamford, Connecticut headquarters clashed with PARC's freewheeling hippie culture.

This is another classic case of the innovator’s dilemma for big corporations. Clayton Christensen names the following attributes as their downfall: (1) Current customers aren’t served by new market; (2) New market is too small for large companies; (3) Use of new technology isn’t fully known yet; (4) Processes that help them with current business hurt them with new business; and (5) New technology isn’t good enough yet to meet higher-end market demand.

Almost all of these attributes can be applied to Xerox and their PARC subsidiary. PARC, in essence, had too much resources at its disposal. Apple was serving a different customer base and was very nimble. They had no choice but to deliver a ship-ready product that they can make a profit on under their current cost structure. Xerox was devoted to their current money-makers and had little incentive to focus on the small, untested personal computer market. “Maybe the only lesson of the legend of Xerox PARC,” concludes Gladwell, “is that what happened there happens, in one way or another, everywhere.”