The Innovations of Apple: Part I

Apple is an incredibly creative, innovative company, and is usually at the top of people’s minds when it comes to new consumer technologies. So for the rest of this post, I’ll examine if and why Apple’s products are disruptive.

Disruptive Portable Music?

Before MP3 players, the only real option for portable music was a CD player. The first MP3 players were introduced in 1998, and had very low capacities. They could hold at most one or two CDs worth of music. In 2000, Creative released its NOMAD Jukebox, which had a capacity of around 1,200 songs. However, it was expensive and had limited usability.

The first generation iPod (5GB) was released in 2001 and could hold an average of 1,000 songs, or about 79 CDs at an equivalent quality. The cost of music (content) was low at first: consumers who already had a CD collection could transfer their songs to the iPod, or download them from the (usually illegal) filesharing programs on the internet.

The total cost per portable song for an iPod 1G was $1.48 or $0.39 if users converted old songs. This compares favorably to a CD player’s $1.95 cost per song (assuming someone can carry around a maximum of 10 CDs without it becoming too much of a burden – see notes for details). Despite this ability to carry more music for an incrementally cheaper cost, like earlier players the high total cost of the device—and the lack of convenience to use its capacity—confined sales to “fist adopters” and high-end users who were willing to convert their old music collection.

So at first, the iPod was a sustaining innovation relative to other portable music devices. Although it wasn’t made by a current industry leader, it was a breakthrough improvement upon other portable music devices and the performance metrics that customers valued (quality, capacity, cost per portable song, etc.).

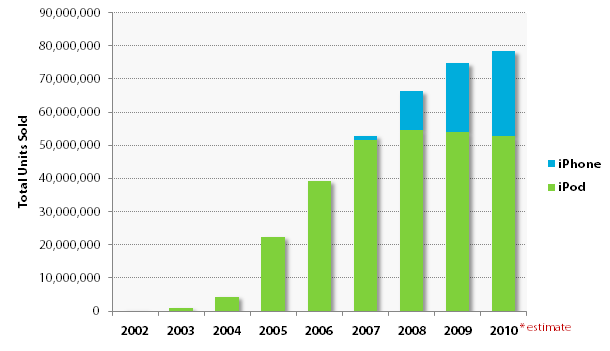

The release of the iTunes store in April 2003 significantly reduced the barrier of purchasing and managing new music/content for the iPod. The store would offer individual songs for 99 cents or an album for $9.99 (also comparing favorably to CDs). As you can see in this chart, iPod sales go from an average of 123,000 a quarter to 545,000 a quarter immediately after the store’s release.

Although the iPod itself was not disruptive, the iPod/iTunes combination seems like a low-end disruptive innovation relative to both CD retailers/distributors and (to a lesser extent) record companies. It disrupted the “channel” of the music industry by coming in at a lower price point, a much lower cost structure, and more convenience for the end user. *

(* I should note that, unlike some innovations, the iPod & iTunes don’t neatly fit into any of Christensen’s categories. In the end, labels don’t really matter, though it does help to see where the product fits in and where its evolution may take it in the future.)

The value network of the industry was well situated before iTunes came along: Artists > Record companies > Music devices / CD manufacturers > CD retailers. Each constituent made money this way, and so their strategies were focused on lowering costs and satisfying current customers (CD purchasers). In the new network, the iPod/iTunes combo filled the roles of medium, device, and distribution. But it also had the ability to bypass record companies and distribute directly from artists. So although the record companies still play a major role, by disrupting their product channel iTunes forced them redefine how they made money.

Performance Oversupply

According to Clay Christensen, performance oversupply occurs when the performance of a technology under a certain attribute (whether it be quality, capacity, reliability, etc.) increases beyond what the market demands. Once market demands of that attribute are met, other attributes whose performance has not yet satisfied demands becomes more highly valued. Companies pursuing both sustaining & disruptive technologies will seek to use this “new” attribute to sustain and differentiate their product.

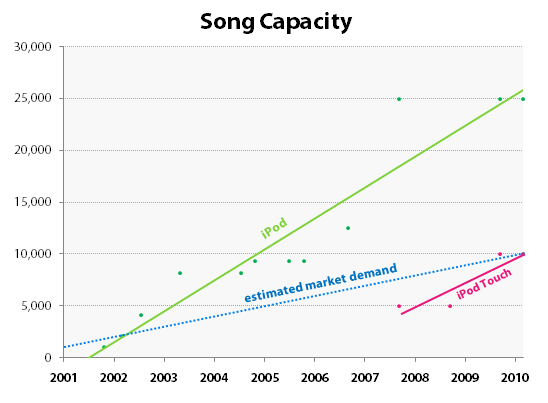

Both song capacity and purchasing convenience were what vaulted the iPod past CD players and other music devices. But as seen in this chart, the metric of song capacity (and in turn cost per song) quickly surpassed average market demand (though high-end users were still served by this ever increasing performance).

A typical pattern of attributes, according to Christensen, is the evolution from functionality to reliability to convenience to price. Price competition is usually the endgame once each dimension of performance has been fully satisfied. For the iPod, it seems that the most important attribute evolved from capacity to convenience to features—and finally to price:

When the iPod was competing for features (photos, bigger screen, video playback), it essentially branched out into the iPhone and iPod Touch. Although both have much less capacity than an iPod classic, they have enough capacity to satisfy average market demand along with the features that are now more important.

While the iPhone is a completely separate product, it evolved from the iPod’s value network and technology, and was an improvement upon existing cellphone designs. It is a sustaining innovation relative to both iPods and smart-phone devices. The iPhone (& Touch) transformed the iPod from a portable music device into a portable communication / productivity / entertainment device (with iTunes and the new app store acting as content distributors).

I’ll talk more about the iPhone—and where the iPad may fit in—in part II of this post.

Notes: CD measures assume 13 average songs per CD, with each person able to carry 10 CDs at a time. Cost per CD in 2001 was $14.19, $13.85 in 2002, $13.63 in 2003, $13.29 in 2004, and assumed $13 thereafter. A good quality CD player (Sony Walkman) cost $112 in 2001. So, cost per portable song would be (112 + 14.19*10)/130 = $1.95.

Average song size is 5MB (Apple figures size is just over 4MB, though the actually average is probably higher). If you assume that for every 30 individual songs purchased the user purchases 1 album (13 songs for $9.99), the average cost per song is 92.3 cents. For the measure of song capacity, to partially adjust for the inclusion of “other media” (photos, videos, etc.) after the iPod 4G, it is assumed that 25% of the iPod’s capacity is not used for music, and in that space each “song” is an average of 100MB in size.

For any number that is estimated above, I tried to err on the side of caution so that if I was off it wouldn’t necessarily invalidate any conclusions.