Managing Modes of Effort

This is the second essay in the Build Series.

The first was Wayfinding Through the Web of Efforts.

Making progress — in society, a team, or life — isn’t straightforward most of the time. Knowing where you want to go is generally the first step, but the destination can be very broad. And even if there’s a specific goal, the path to get there may be very indirect.

As strategy transitions into execution, it’s important to understand how these attributes affect progress. If an effort is managed or guided the wrong way, it may be doomed to failure no matter how difficult it is.

Project management as a discipline works great, but not with everything. Managing large, more uncertain endeavors in particular has been problematic recently. The wide-scale ongoing effort to fight COVID-19 and return the world to normalcy brings this challenge front and center.

Why are certain efforts harder than others and how do we navigate them? How were we able to accomplish such large scale collaborative efforts such as the Apollo program or Manhattan Project, but can’t do the same thing for curing cancer?

If we want to build, we need to understand the answers to these questions. The following is a framework for classifying efforts by the certainty of both their objectives and the paths to achieve them. Knowing which “mode” an effort is in is critical to understanding and managing its progress.

Classifying efforts

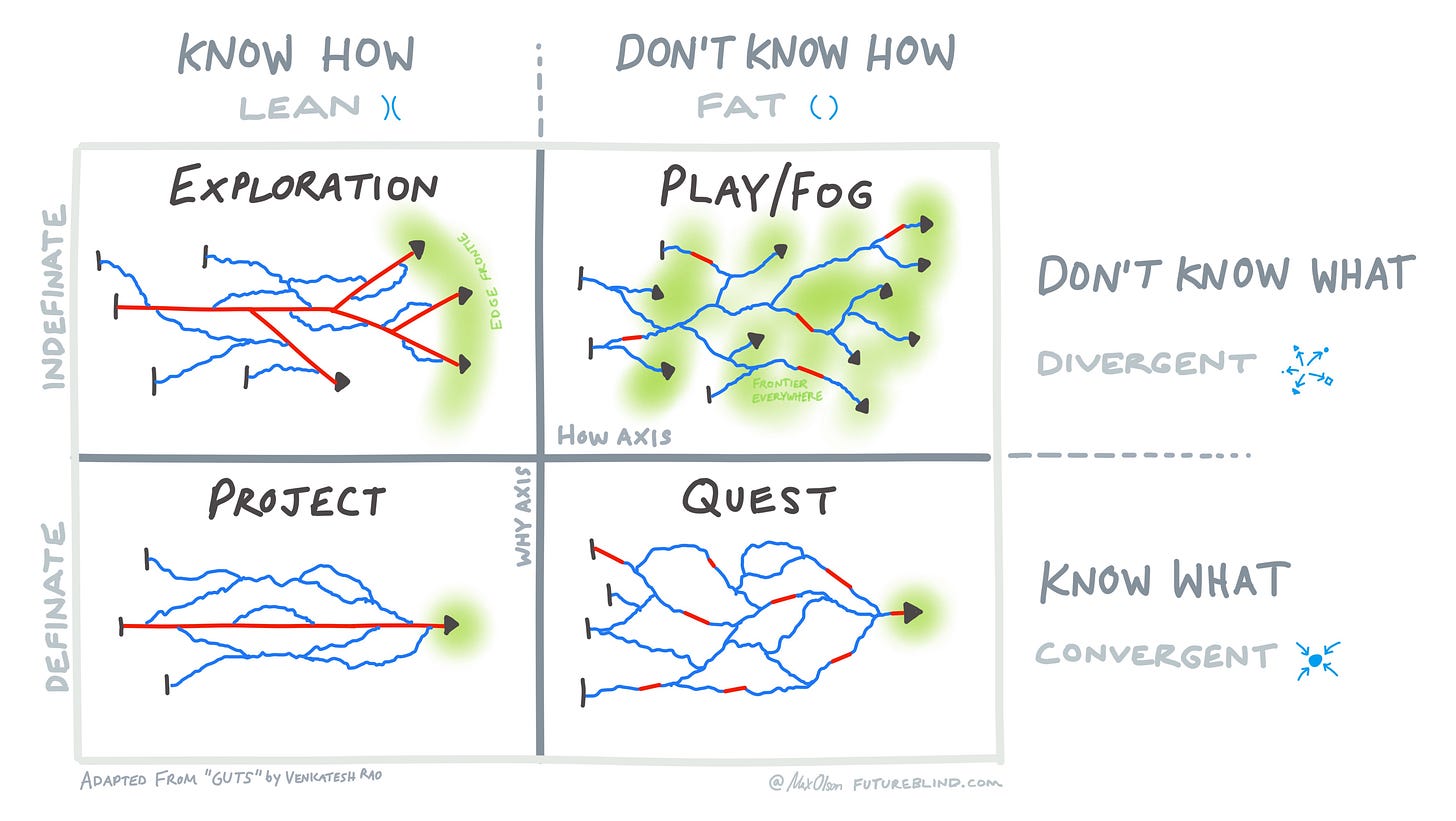

How do we classify efforts into modes? The best paradigm I’ve come across is the how/what quadrants.

In his 1994 book “All Change!”, Eddie Obeng described 4 different types of projects along with the difficulties and peculiarities of each: quests, movies, painting by numbers, and fog. It turns out putting a project on both the know how and the know what scales tells you a lot about how it should be managed.

Venkatesh Rao explored the concept much further in his essay on the “Grand Unified Theory of Striving”, pulling in other ideas like convergent thinking, critical paths, and lean methodology. Venkat’s visualization of the critical paths and point frontiers of each quadrant is a particularly insightful way to think about the concept.

Defining the dimensions and modes

Here’s how I’d describe the axes of the 2×2:

“Why”-axis — Know what vs. don’t know what. Do you know what the goal is? How specific is the desired outcome? Not knowing the goal (or having a very broad idea) is in the realm of divergent thinking: there are many potential solutions and progress can be non-linear. It’s the exploration phase of the explore vs. exploit tradeoff, searching for goals or areas of value.

Knowing what and why is in the realm of convergent thinking: there is a single “correct” solution or destination. It squarely aligns with Peter Thiel’s deterministic approach of viewing the future: “There is just one thing—the best thing—that you should do.”

Horizontal-axis — Know how vs. don’t know how. Is it known how to accomplish the goal? Are the bottlenecks or resource-sensitive parts generally understood? When you know exactly how to accomplish something, there is a clear critical path1 (the red lines in the diagram below). Other paths of effort may still be required, but they are oblique with more slack, running parallel to the critical path.

Knowing how allows you to operate lean because you can—in theory—use the least amount of resources necessary to get the job done. In the fat mode of operation, you don’t really know how to reach your goal. You can’t be efficient because you don’t know how to be, and there will be a lot of slack in the system. The path is determined opportunistically as you go, with critical paths only in smaller subsections.

Each quadrant can be described as follows:

Play/Fog — Your outcome isn’t precisely defined or how to get it. There are some boundaries, but within them value is potentially anywhere, and there’s no concrete method to find it. Trying to optimize here can actually hurt — Venkat: “Being too efficient along the way can be counterproductive: your critical path might zoom through the most valuable zone.”

Solving climate change, curing cancer, or achieving happiness in life all qualify. Depending on personality, being in this quadrant can be either liberating or deadly. “Everything seems possible but I can’t really see where I am going,” described Eddie Obeng. “It’s a bit like trying to make your way in a fog.”

Quest2 — You know exactly where you want to go, but the goal is too complex to know how to achieve it yet. Many paths may have to be taken, some making progress towards the final goal, some being false-starts or dead-ends. Venkat: “you can only optimize bits of the system at a time[…], so you can only have short stretches of locally critical paths.”

Many venture-backed startups fall in this category. A definite goal or vision is in mind from the get-go, but it’s unknown how exactly to get there. The only way forward is adaptive experimentation.

Exploration — There is a frontier of value—an area generally defined as success—but any specific outcome isn’t necessarily planned for. You also know how to make progress even though events along the way may lead to completely different destinations. Effort is based on a method. This is probably the strangest quadrant in that it’s the one that people/orgs are least used to.

Examples include movie producers, 1400-1800 era explorers, and oil prospectors. Some startups also begin in this quadrant: It’s unknown what business model they’ll eventually land on, but the paths for getting there are relatively clear. (Lean startups, agile customer development, specific biz model playbooks, etc.)

Project — The traditional “project” they teach about in business school. You know exactly what you want and how to get it — the rest is execution. There’s a single critical path that can be managed for efficiency. Most modern construction projects classify.

All efforts are nested, and so are their modes

As we know from the last essay, all efforts are nested and multi-scale.

On the web of abstraction, efforts generally descend from Play at the top (abstract), to Quests, Explorations, and finally Projects at the bottom (concrete and direct). Play is the most zoomed out, and other modes are zoom-ins along the why or how dimensions. A smaller-scale Project might fit somewhere in larger Quest, which could be part of an even wider-scale Play effort.

Here’s an example of one of these chains of effort for SpaceX. Note that their actual mission is “Make humanity multiplanetary,” which is the highest level that SpaceX goes in abstraction — but you can always go higher.

In a higher-level Play/Fog objective, when you focus on a particular sub-goal or patch of value, you’re restricting the ends, transitioning to the Quest mode of effort. Or you could restrict the means by narrowing down a method of operation, and moving into Exploration mode. If you zoom in far enough you can always get to a Project.

Many successful research efforts operated in the Play mode, even if the organization above them had a specific goal — Bell Labs, Xerox PARC, OSRD, DARPA, etc. Within them these efforts could have teams or individuals working across the spectrum from Play (serendipitously experimenting) to Project (executing on specific, short-term goals). In the divergent modes of Play and Exploration, if an area of high value is potentially discovered, the goal for part of the organization becomes more focused as a Quest or even Project if the methodology is known.

The leaders of these research efforts did not manage to deadlines or find bottlenecks to put pressure on. They hired talented people, gave them the support they needed, and let them build. This leads us to how each mode is managed.

For another case study on the COVID-19 response, see footnotes.3

Different modes call for different management styles

How should each mode get managed? It seems like common sense that you can’t manage a research lab the same way you manage a construction project — but why? Let’s start with thinking about the ends of both spectrums.

On the “how” spectrum:

Lean — When you know how to do something (likely because it’s been done many times before) you can operate lean. You have to be good at managing to the method, then coordinating and communicating effectively to stakeholders. Focus and consistency are key. These are Venkat’s “mercenary lean-six-sigma stonecutter types”.

Fat — Making progress without knowing exactly how means you’re operating fat. Adaptation is the key here. You have some kind of “fitness function” or indicator of progress, and you take incremental steps, adjusting your path as you go. Scope is frequently reduced for shorter-term, leaner goals. All of this lends itself to a more decentralized style, focusing more on leading talented people rather than telling them exactly what to do.

On the “why/what” spectrum:

Divergent — Not knowing the exact destination in the top quadrants requires divergent thinking. Managers need to accept unplanned diversions and more freewheeling creativity. Similar to the “fat” half, there has to be some indicator of success — a definition of boundaries and a guide to level of progress. But otherwise serendipity and opportunism are key here. Focus should be on learning to learn and assigning roles rather than tasks.

Convergent — When you know exactly what the goal is, you can converge. Management can be more process-oriented, focusing on alignment and assigning tasks or projects. Some opportunism can be accepted but paths must be regularly pruned if it’s not clear they’re moving closer to the objective. These are Venkat’s “missionary types”.

So for the individual modes, you can just combine the respective styles from each spectrum. Play requires decentralized leadership of creative people, lots of trial and error, and embrace of serendipity. Projects require strict focus, coordination and consistency of operation (think military).

These differing management requirements are why McKinsey consultants have a hard time running research efforts and entrepreneurial liberal arts school dropouts have issues running a lean manufacturing plant.

In his recent book Loonshots, Safi Bahcall put it this way: “Wide management spans, loose controls, and flexible (creative) metrics work best for loonshot groups. Narrow management spans, tight controls, and rigid (quantitative) metrics work best for franchise groups.”

I think it’s possible for a manager to have the ability to lead and navigate multiple different modes of effort. But due to the different skillsets involved, it’s probably very rare. Just like it’s rare to find a startup founder who can successfully navigate the transition from a handful of people in a garage to large public company.

In the intro, I asked why certain efforts are harder than others — like curing cancer vs. putting a man on the moon. The simple answer is that these efforts remain too abstract, both in means and ends, to chart a path to the destination.

Curing cancer has some boundaries but is still fairly abstract. All types of cancer? What is the form of the cure — preventative, genetic, pharmacological, surgical? Compare this to Kennedy’s objective of “achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth,” the rough elements of which engineers understood at the time. This takes nothing away from how challenging and risky it was to get there — but it was a Quest as opposed to a Fog. The progress indicators were much clearer and could be broken down into more concrete efforts.

Know your mode and manage appropriately

When undertaking any effort, from small personal project to large collaborative endeavor, ask:

What level of abstraction is the objective in and what are the levels above it? Ask why. Context is very important — you don’t want to be solving the wrong problem.

What mode is the effort in? Where is it on the what and how spectrums?

What does the mode imply about how progress should be managed?

How can it be broken down? Break it down into smaller, more concrete efforts. Even if the primary effort is in a “fat” quadrant and you don’t know how to get to the final goal, you can take incremental steps by solving parts of the problem and learning as you go. All short-term goals should be Projects.

Header photo by Alexander Andrews on Unsplash.

Critical path = the chain of interdependent tasks that requires the most amount of resources (time, money, effort, etc.)

I use Obeng’s term here as it more accurately describes what it’s doing. “Muddling Through” is also a mouthful to keep repeating.

Case study: COVID-19 response. Continuing from the sample hierarchy of efforts in the last essay, let’s take a look at the modes of effort in the fight against the pandemic. How do we prevent more people from dying? How do we get the economy and people’s lives back to normal?

Stops deaths and reopen the economy — The overall response has and will continue to be in the upper right quadrant, Fog in this case rather than Play. We have a general direction — “less deaths, more jobs” — so we’re not at the extreme north on the Why-axis. But there is no viable, concrete vision of what the post-COVID future looks like that doesn’t include a large amount of deaths.

Finding a cure — Quest. The general goal is known: When someone contracts COVID-19, they are able to be given cost effective medication that kills the virus or renders its effects harmless. Methodology for parts of this effort are known, but there is no global critical path.

Testing potentially effective treatment — Project. As part of finding a long-term cure, we have to test drugs that can potentially be either a cure themselves of part of an effective treatment cocktail. The goal here is collecting enough evidence to confirm or deny a certain drug is effective. There are many ongoing efforts on this front in addition to vaccines.

Distribution of adequate PPE — Project. The goal is straightforward. We know how to do it: manufacturing these items at scale is very simple and the world has been doing it for decades. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy — especially not so, it seems, in the U.S.

Creating traditional vaccines — Exploration. Vaccine creation is as clear of a case of Exploration. We know how to create and test vaccines, but we don’t know which we’ll end up at or will provide the most value. Entities with a lot of resources like governments and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have the added benefit of enabling each critical path to be done in parallel (becoming a group of Projects), with many different destinations reached at roughly the same time, and the best one or few chosen.

Fast, ubiquitous testing — Quest. Cheap, highly accurate tests available at every drugstore and in workplaces. We don’t know how exactly to create these miracle tests yet, but the effort is inching closer to becoming a Project. As I understand it there are multiple potentials for a breakthrough in the research/testing phase.

Wide-scale availability of existing tests — Project. We have proven existing tests, namely RT-PCR (the one you see hospitals and drive-thru stops swabbing for). Finding where the bottlenecks and limiting resources are in this supply chain and executing on them is straightforward, but seemingly not easy.

This is an example of breaking an effort down into a hierarchy and classifying each into modes. It forces you to think about each part to better decide what the next steps are, and how to manage them.